Inspiring Stories

'I Know That I'm a Miracle': Jennie Edmundson Patient Thrives After COVID-19

Published: Nov. 25, 2020On a warm day in September, Morris Sandoval arrived at St. Anthony Regional Hospital in Carroll, Iowa.

He was there for his semiweekly physical and occupational therapy appointments, meant to help him regain the strength and manual dexterity he lost while sick with COVID-19.

Morris was running late but couldn’t easily explain why. He hadn’t forgotten or been delayed – he simply didn’t leave his home in Denison on time. Since beating the disease, he said, his mind has been fighting to recover, too. At times his brain feels like it’s working in slow motion.

Morris quickly got to work with an occupational therapist, starting with a hand pedal exerciser before moving to a more taxing heavy rope workout. Then it was on to lifting 10-pound weights on and off of raised platforms – an exercise intended to simulate his work at the dry ice plant in Denison.

“How ya feelin’?” Chris Josko, OTD-RL, asked at the next station as Morris grabbed and twisted a short rubber bar.

“Tired,” he said with a laugh between heavy breaths. Then he pushed on with determination.

Considering where Morris had been, this was nothing. After all, as he lay in a Methodist Jennie Edmundson Hospital bed three months earlier, his family wondered if he would even survive.

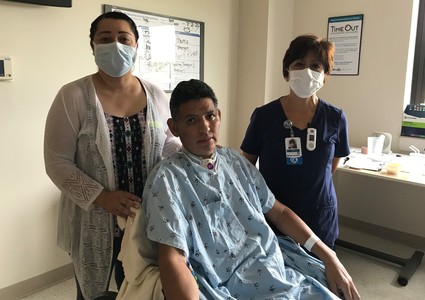

Morris and his family before he became ill with COVID-19. Family photo

A Life-Changing Illness

Life was good for Morris and his wife, Rebeca Ayala, in the spring of 2020. His home renovation business was doing well, and he had taken a job at the plant for the health insurance benefits. Always on the move, Morris had plans to finish remodeling their Victorian-style home that year.

“I was used to doing it fast and strong, seven days a week,” the father of five and grandfather of two said. “I felt happy. Everything was really good.”

In May, the family’s world was turned upside down. Morris’ daughter and son-in-law got sick, and soon Morris and Rebeca were experiencing fevers, chills, headaches and diarrhea. On May 16, 44-year-old Morris tested positive for COVID-19.

“I thought it was just going to be like a cold,” said Morris, who was otherwise healthy. “But it wasn’t like that.”

Rebeca and the rest of the family recovered while isolating, but Morris' condition worsened. He began having breathing problems and felt dehydrated. On May 27, he went by ambulance to the Denison hospital, where doctors determined he was suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) – fluid buildup in his lungs. With Morris’ lungs failing, doctors put him on a ventilator. As Morris slipped into unconsciousness, he saw Rebeca and his brother-in-law looking at him through a hospital window.

“That’s my last memory.”

Methodist pulmonologist Dr. Sumit Mukherjee

More Questions Than Answers

Later that day, Morris was transferred to Jennie Edmundson’s critical care unit, where pulmonologist Sumit Mukherjee, MD, led the team caring for Morris and other COVID-19 patients. They immediately went to work, using the latest treatments, including convalescent plasma from COVID-19 survivors and the antiviral drug remdesivir.

“It was definitely an evolving process, and the playbook was being written as we were going through this,” Dr. Mukherjee said. “He received everything that we knew was working for COVID-19.”

With the help of a ventilator, Morris was alive. But he was heavily sedated and not lucid. Rebeca called the hospital daily for updates, and she traveled from Denison to Council Bluffs every day to be by Morris’ side after his COVID-19 isolation precautions ended in mid-June.

As the days stretched into weeks, there were more questions than answers. Could Morris recover? Would he ever return home? Would he even survive?

Morris’ family and the critical care staff rode a roller coaster for weeks. There were several conversations about the goals for Morris’ care and if it was doing more harm than good.

“But I couldn’t ever say we have this steady downward trend,” Dr. Mukherjee said.

Morris would be unresponsive one day. Another day he would weakly squeeze his fingers together.

“It was enough to say that we need to keep fighting and keep going,” Dr. Mukherjee said.

"The Voice for Latino Patients"

Through bad days and encouraging ones, Rebeca found strength in Jennie Edmundson’s staff members. Among them was Julia Tyson, a Spanish language interpreter, who helped Rebeca during deeper conversations with medical staff members about Morris’ care.

Tyson describes herself as “the voice for Latino patients.” But she did more than bridge the communication gap, said Rebeca, who, along with Morris, grew up in El Salvador. The women bonded during their time together, talking about Morris’ personality, their families and Tyson’s favorite Peruvian dishes.

“She was like family because nobody else could be with me during that time,” Rebeca said.

Tyson saw an even stronger bond when Rebeca and Morris were together.

“The strength and faith that Rebeca had that her husband would recover from this virus – I could feel her faith,” Tyson said. “The way that she talked to him, she showed that she really loved her husband.”

Answered Prayers

On June 17, Morris was briefly transferred to Methodist Hospital to have a tracheostomy. He returned to Jennie Edmundson the next day and showed some positive signs – small movements, including raising his eyebrows.

“That told us that maybe he was in there,” Dr. Mukherjee said.

But in the following days, Morris returned to his confused, unresponsive state, even as staff lowered his medications and sedatives. Dr. Mukherjee feared Morris may have suffered a brain injury from lack of oxygen. Tests showed some slowing of brain activity, but nothing conclusive.

Rebeca admitted that doubt began creeping in. She wondered if Morris would leave the hospital alive.

“There were moments when I was thinking, ‘Where is God?’” Rebeca said. “It’s something that I was thinking in those moments, but my faith was strong. And keeping this faith made me feel that he was going to overcome this.”

On June 29, her prayers were answered.

“He opened his eyes, and I asked him, ‘If you know me, raise your eyebrows.’”

And he did.

Rebeca called critical care nurse Amy Waldstein, BSN, RN, to the room. Together, they asked Morris to squeeze their hands. Weakened after more than a month fighting COVID-19, he didn’t respond. But when asked to raise his eyebrows, he did.

“In that moment, I started saying to God, ‘Thank you. Thank you for this,’” Rebeca said.

The Road to Recovery

For the critical care staff, it was a pivotal moment. There was work to be done, but Morris had come through the worst of COVID-19.

“I was totally confident that we were headed in the right direction now,” Waldstein said. “Once he started showing signs that he was OK mentally, we started challenging him pretty rapidly to wean him off the ventilator.”

The vent was removed for good and replaced with supplemental oxygen on July 1. Meanwhile, nurses, respiratory therapists, physical therapists and occupational therapists were working with Morris on breathing treatments, sitting and standing on his own, and other activities.

“Once people demonstrate that they’re able to follow commands and that they’re able to work with us a little bit, it’s like somebody finds the big green go button and hits it,” Dr. Mukherjee said. “It’s an exponential improvement.”

In the weeks before, while Morris had been unconscious, Waldstein had been another shoulder for Rebeca to lean on. Now the self-described drill sergeant changed roles, pushing Morris to do more to regain his strength. Her demanding care, at times straddling the line between encouragement and healthy discomfort, are some of the first memories Morris has after waking up.

“Amy, she was tough, but she loved me so much,” he said. “She wanted me to be better. She’s amazing.”

The hard work was paying off. On July 2, Morris had a speaking valve attached to his tracheostomy tube, and Dr. Mukherjee made plans for discharge.

The next day, Morris was wheeled out of Jennie Edmundson and was reunited with much of his family for the first time since May. Surrounded by staff members and local reporters, Morris, Rebeca, Dr. Mukherjee and Tyson shared the inspiring story, and Morris raised his hands to applaud his care team.

“I know that I’m a miracle. And I know very well what angels God put in my life,” Morris later said. “Dr. Mukherjee is one of my heroes, and all the nurses that were there. I’ve never received so much care from people like them.”

Unforgettable Care

While many COVID-19 survivors have lung issues and chronic fatigue, Morris has exceeded expectations. Dr. Mukherjee will continue to monitor X-rays of Morris’ lungs but is optimistic about his physical health. There are also cognition problems COVID-19 patients can face. Morris is frustrated by how his mind seems to work slowly at times, and he’s working through insomnia, anxiety and nightmares. But like so many challenges before, he’s determined to overcome them.

“He has had such a great, positive attitude through the whole process,” Dr. Mukherjee said.

Morris now has his eye on returning to the plant, building up his business and finishing work on his house. In these months away from work, the Jennie Edmundson Foundation assisted his family financially through its COVID-19 Response Fund. Coupled with his health insurance, which kicked in two weeks before he became ill, that assistance has allowed him to focus on healing.

Looking back on the medical treatment, language services, financial assistance and emotional support, Morris marvels at the level of care he and his family have received.

“I’m so impressed, not only because I have my life. But the thing is, I’m so important to that place,” he said. “Being in the hearts of the people who work at the hospital is important to me. It makes me strong and makes me feel valuable. That’s something that survivors of COVID-19 need.”

Photos and video by Daniel Johnson

More Resources

- Read more about Methodist's language interpreters.

- Read more from the winter 2020 issue of The Meaning of Care Magazine.